최서희 _ 막지리 우체국

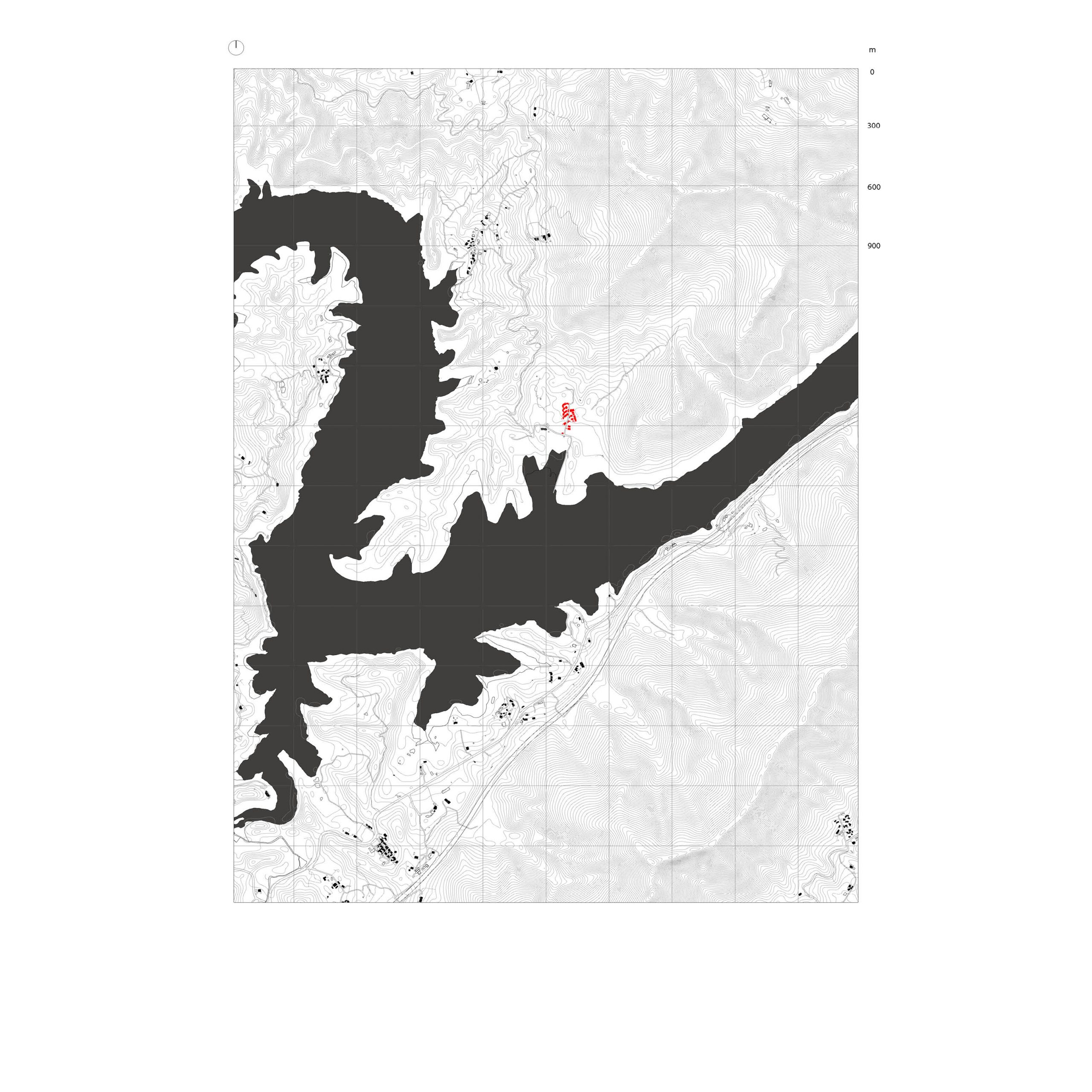

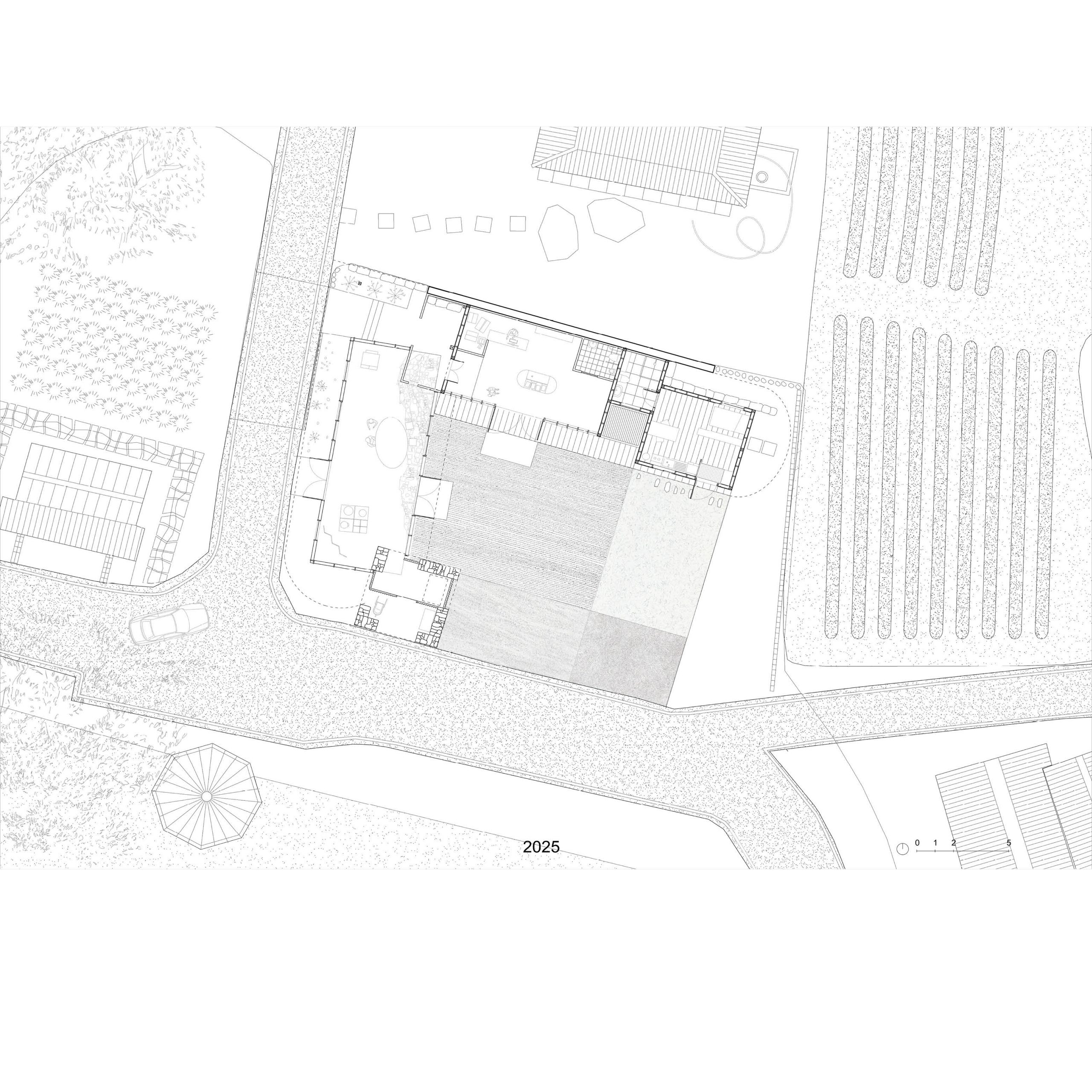

충북 옥천군 군북면 막지리는 2025년 기준 인구 25명, 평균 연령이 74세인 마을이다. 인구 감소

추세에 따르면 2040년 이후 이곳은 급격히 쇠락하고, 마침내 사라질 것이다. 지역 소멸이 사회적

위기라면, 그 단절과 상실의 감각은 결국 개인이 감당해야 할 몫이다. 이때 건축은 무엇을 할 수

있을까?

현대 사회의 위기는 단일한 해답을 요구하지 않는다. 근대와 달리 건축은 더 이상 주도적 해결사가 될

수 없다. 우리는 점점 더 많은 기능을 실패하고 받아들이며, 자연과 사회를 통제하려던 과거의 한계를

마주한다. 공동체의 소멸과 자연의 흐름을 막을 수 없다면, 건축은 마지막 순간까지 ‘함께 버티는

존재’로 남아야 하지 않을까.

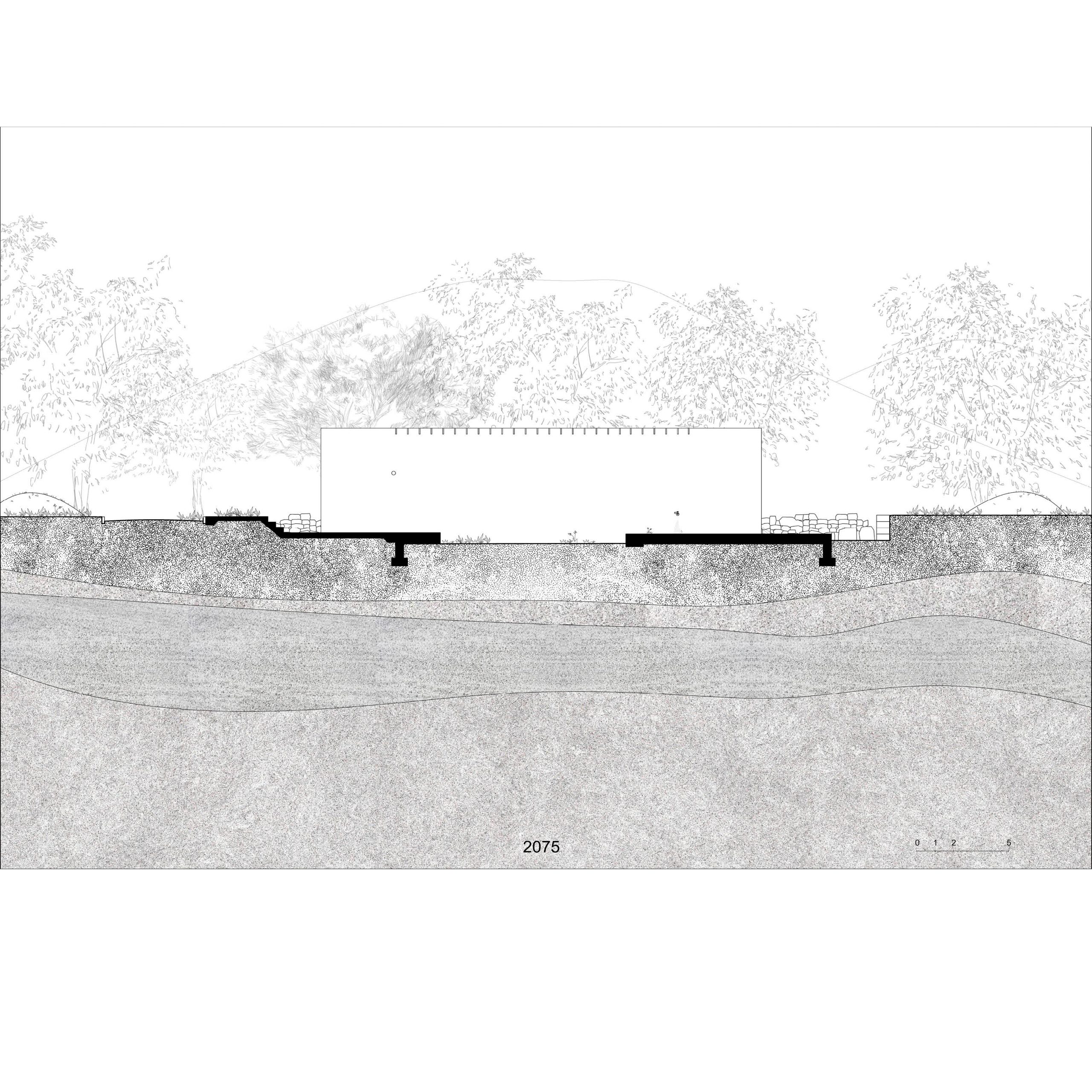

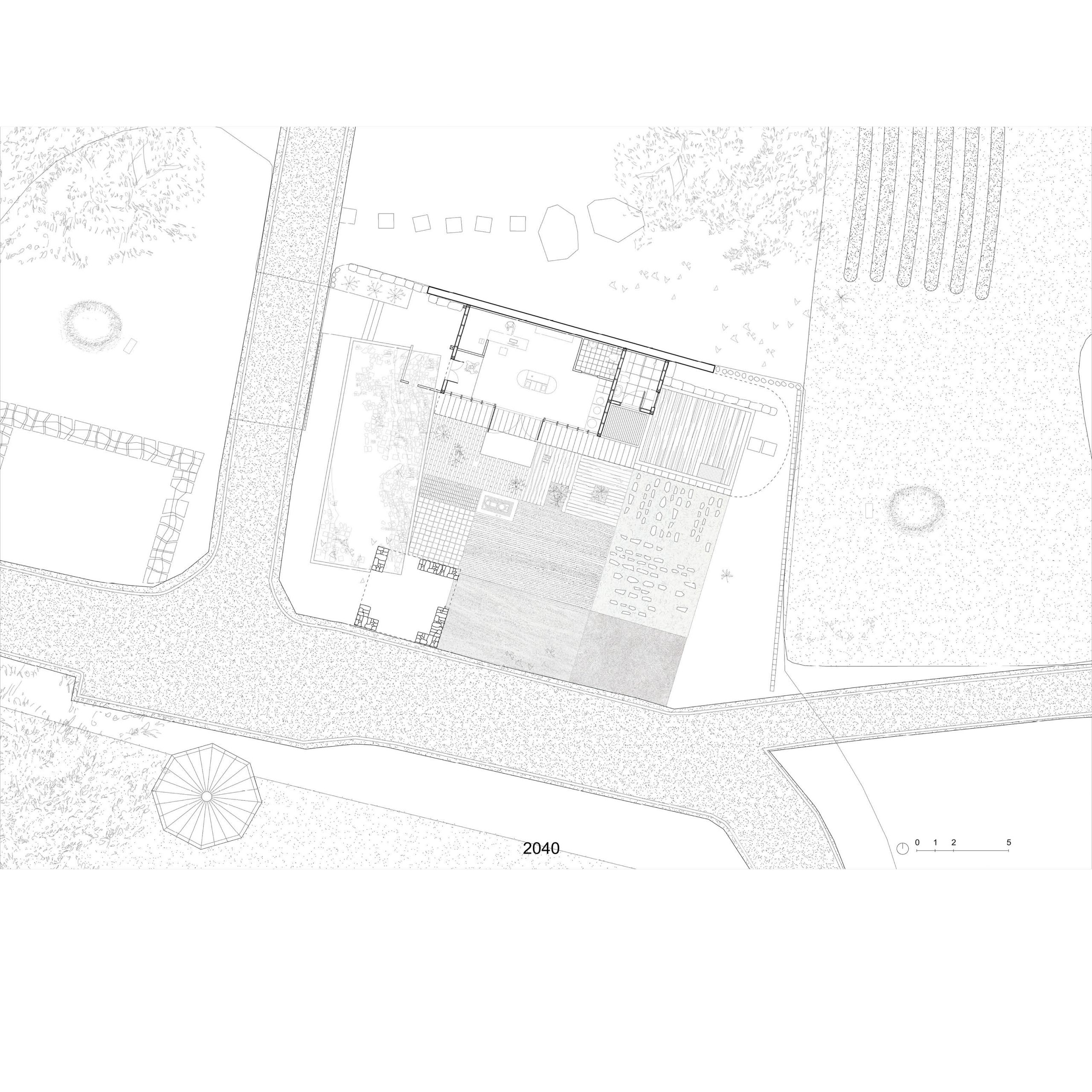

이 프로젝트는 경량 목구조의 숙소와 사랑방은 인구 감소에 따라 차례로 사라지고, 사람이 있는 한

마지막까지 남는 곳은 콘크리트 옹벽에 기대선 ‘우체국’이라는 설정에서 출발한다. 여기서 우체국은

단 한 사람을 위한 소통의 창이자, 마을의 끝을 지키는 구조물이 된다. 모두가 떠난 자리에 남은

옹벽과 돌탑은 무덤과 함께 영원할 듯이 자리한다.

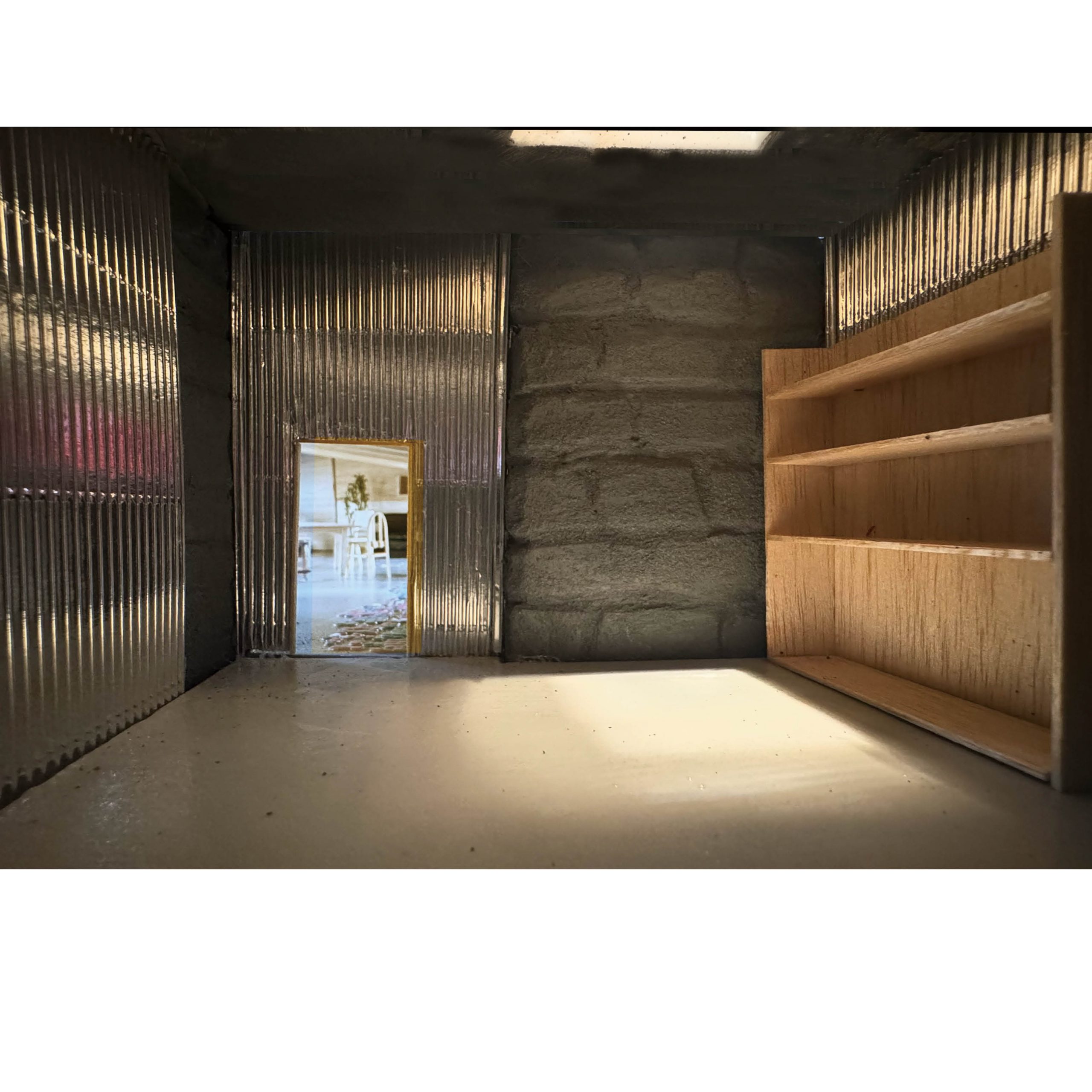

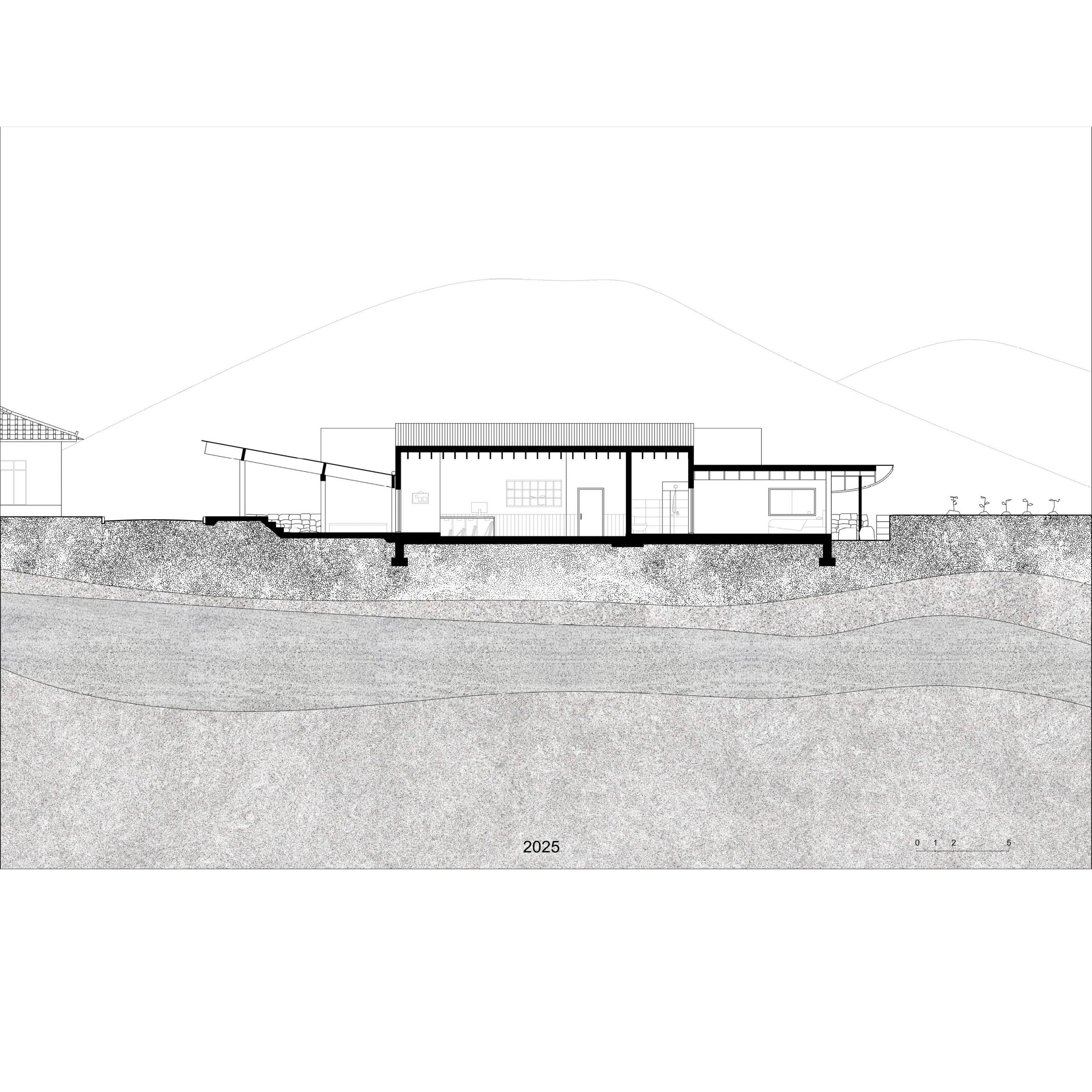

우체국이 기대고 있는 15m 길이의 옹벽은, 근대 기술의 상징이자 균열을 감지하는 장치다. 토사의

붕괴를 막고 자연의 흐름을 멈추며 위험을 예방한다는 명목으로 존재하지만, 실상은 위기의 전조인

동시에 응답이기도 하다. 그 아래 자리한 우체국은 통제와 소멸 사이에서 실존적 동행의 구조를 띠며,

이 간극은 건축이 감당해야 할 윤리의 장으로 작동한다.

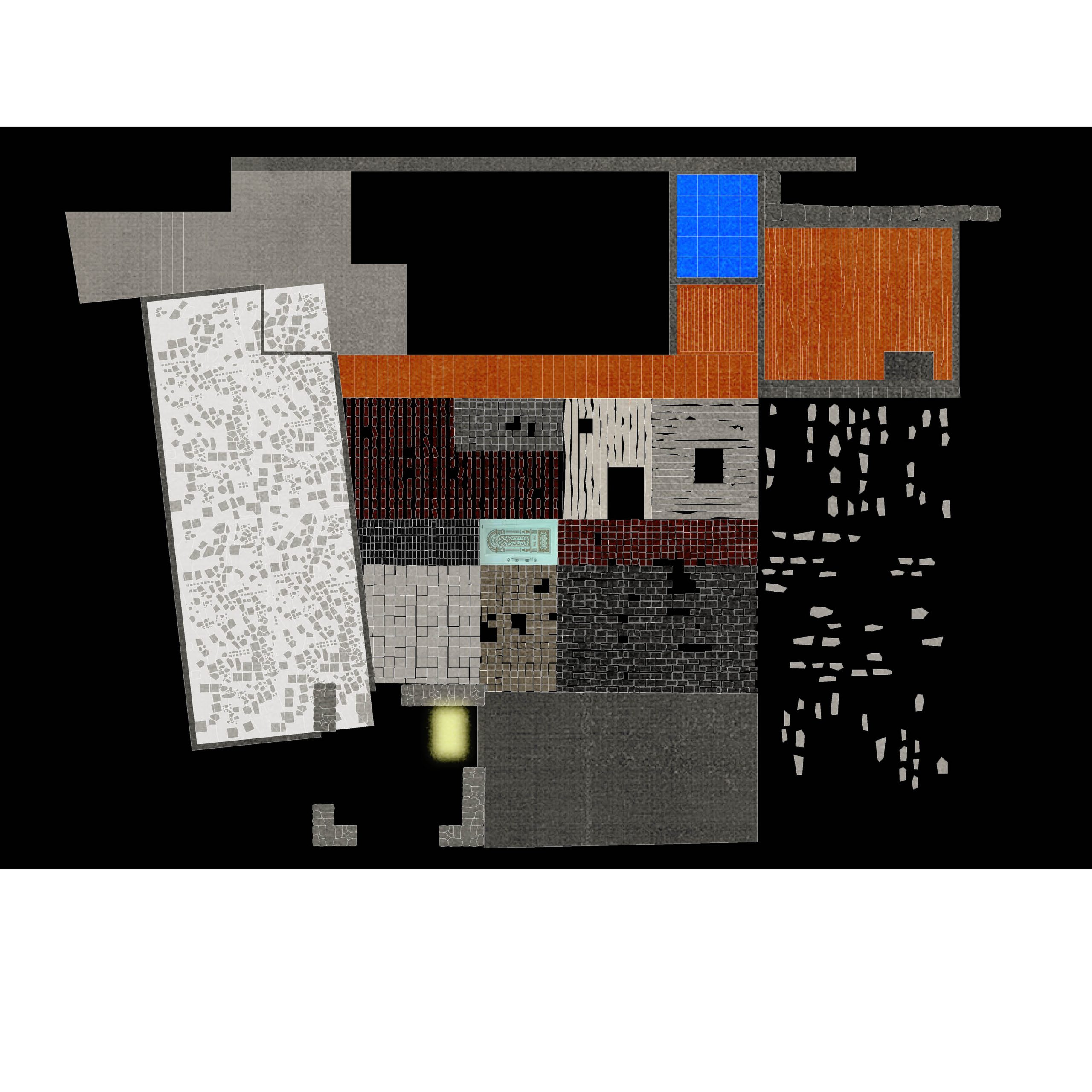

마을을 떠난 이들이 남기고 간 타일, 벽돌, 목재는 중앙 마당을 단단히 다져 양측 무덤 사이를 잇는

작은 광장이 된다. 소멸의 흔적 위에 놓인 이 광장은 사라진 공동체를 기념하며, 죽음과 죽음 사이를

연결하는 마지막 장소로 남는다.

이 프로젝트는 건축이 소멸의 조건을 어떻게 받아들이고 끝까지 무엇과 함께할 수 있는지를 묻는다.

그 물음은 더 이상 ‘지속’이나 ‘복원’이 아닌, ‘동행’과 ‘기억’의 윤리를 향한다.

Makjiri, located in Gunbuk-myeon, Okcheon-gun, Chungcheongbuk-do, is a village of just 25 residents as of 2025, with an average age of 74. According to current trends, its population is expected to decline rapidly and the village will likely disappear entirely by 2040. If the disappearance of a place constitutes a social crisis, it is ultimately the individual who bears the weight of disconnection and loss.

What, then, can architecture do?

The crises of contemporary society no longer demand singular answers. Unlike in the modern era, architecture today cannot offer leading or all-encompassing solutions. We increasingly confront the limits of our past efforts to control nature and society — and fail to overcome them. If we can neither halt the disappearance of communities nor the flow of nature, perhaps architecture should remain as a “presence that holds on” until the very end.

This project begins with the setting of a “post office”, where lightweight wooden lodgings and love rooms vanish one by one as the population dwindles. The last remaining structure leans against a concrete retaining wall — enduring as long as there is someone left.

Here, the post office becomes a solitary window of communication, a structure that safeguards the edge of a vanishing village.

The retaining wall and stone tower, left behind by those who have already departed, are immortalized alongside the village’s graves.

The 15-meter-long retaining wall that supports the post office is both a symbol of modern technology and a crack-detection device. It exists to prevent soil collapse, stop the flow of nature, and mitigate risk. Yet in reality, it represents both a warning of crisis and a response to it.

The post office beneath it becomes a space of existential cohabitation — between control and disappearance.

This threshold becomes an ethical ground on which architecture must act.

Materials left behind by former villagers — tiles, bricks, wood — are used to solidify a small central courtyard, forming a plaza nestled between the graves.

This plaza, situated along the path of disappearance, commemorates a lost community and becomes the final place between death and the dead.

This project asks: How can architecture respond to the conditions of disappearance, and what can it do — until the very end?

The question is no longer one of continuity or restoration, but one of ethics — of accompaniment and memory.