김유정 _ 돼지던스

사람과 가축의 보금자리를 만들어온 건축은 도시의 합리적인 발전이라는 명분 아래 사람과 가축을 분리하는 역할로 축소되었다. 경제적 논리에 따라 최소의 비용으로 최대의 이득을 얻기 위해 축사는 점점 조밀해졌고, 도시에서 멀리 떨어진 교외에 외따로 자리 잡았다. 도시로부터 지워진 가축과 축사는 그 존재 자체가 점차 인식되지 않게 되었고, 그 빈자리에는 축산업에 대한 무지, 오류, 그리고 편견이 대신 자리하게 되었다.

만약 건축이 가축의 존재를 드러내어 그들을 다시 인식하게 하고 그 빈 공간을 메울 수 있다면, 인식의 부재에서 비롯된 오류와 편견, 미신과 비합리를 걷어낼 수 있을지도 모른다. 인간 중심의 질서에서 벗어나 인간과 가축이 새로운 관계를 맺을 수 있다면, 위기인지도 모를 만큼 만연한 "축산업 인식의 부재"라는 위기를 극복할 수 있지 않을까.

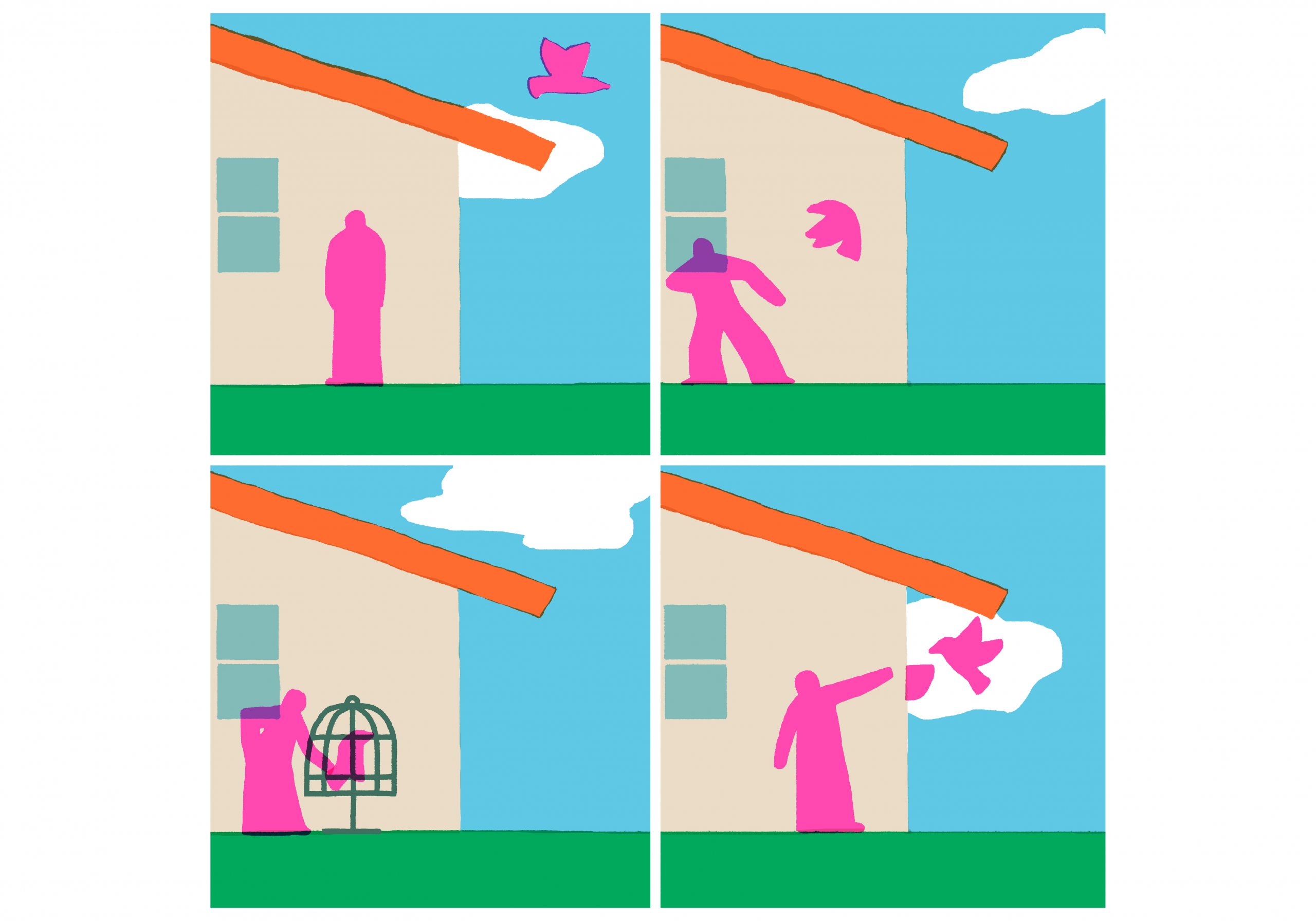

인간과 비인간의 접점을 설정하는 일은 미묘하다. 인간관계와 달리, 심리적 거리감과 물리적 거리감이 비례하지 않기 때문이다. 집 안에서 멀리 있는 새를 바라볼 때, 그 새는 '외부의 것'으로 인식된다. 벽이 두껍든 얇든, 물리적 거리에 상관없이 심리적 거리감은 줄어들지 않는다. 물리적 거리감을 줄이고자 야생동물을 인간의 공간으로 들이면 양쪽 모두 당황스럽고 불편함을 느낀다. 공간이 아무리 넓어도 '침범당했다'는 감각은 심리적 거리를 오히려 더 크게 만든다. 새장처럼 인간의 질서 안에 동물을 두면 물리적·심리적 거리감이 줄어든 듯 보일 수 있으나 한쪽의 생활방식이 존중받지 못하는 관계는 결국 공허한 소유의 감정만을 남긴다.

반면 처마 밑에 둥지를 튼 새와의 관계는 다르다. 필요성에 의해 스스로 처마 아래를 선택한 새는 같은 지붕 아래를 공유하는 주체적 존재로 다가온다. 비록 물리적으로 집의 외부에 있지만, 이 자발성은 서로를 한 공간에서 함께 살아가는 동등한 생명으로 인식하게 한다. 오래전 외양간이 인간의 질서에 가축을 위치시키는 '새장'의 관계를 만들었다면, 지금 우리가 시도하는 또 다른 관계는 공생하는 처마 밑 새와 인간의 관계다.

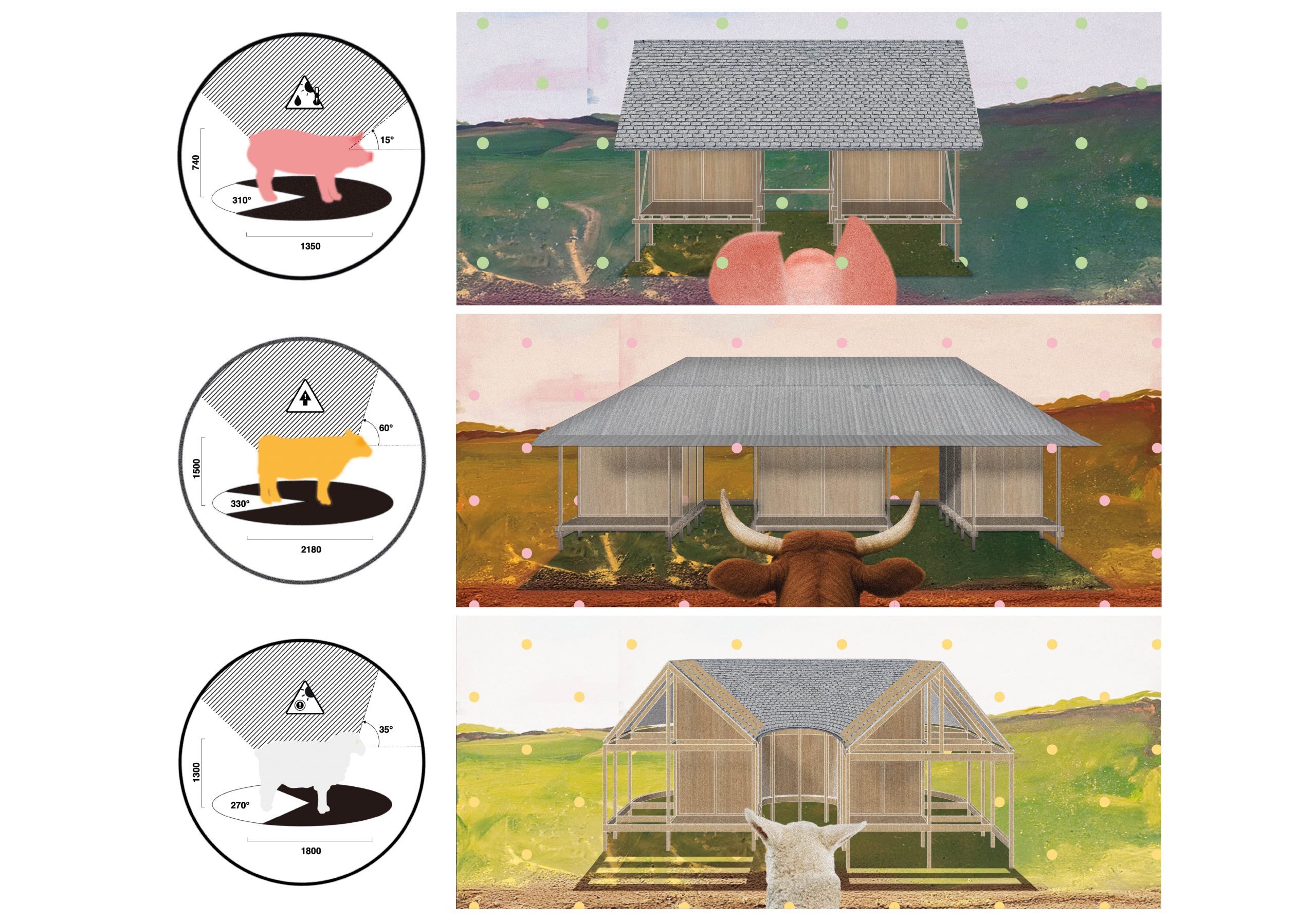

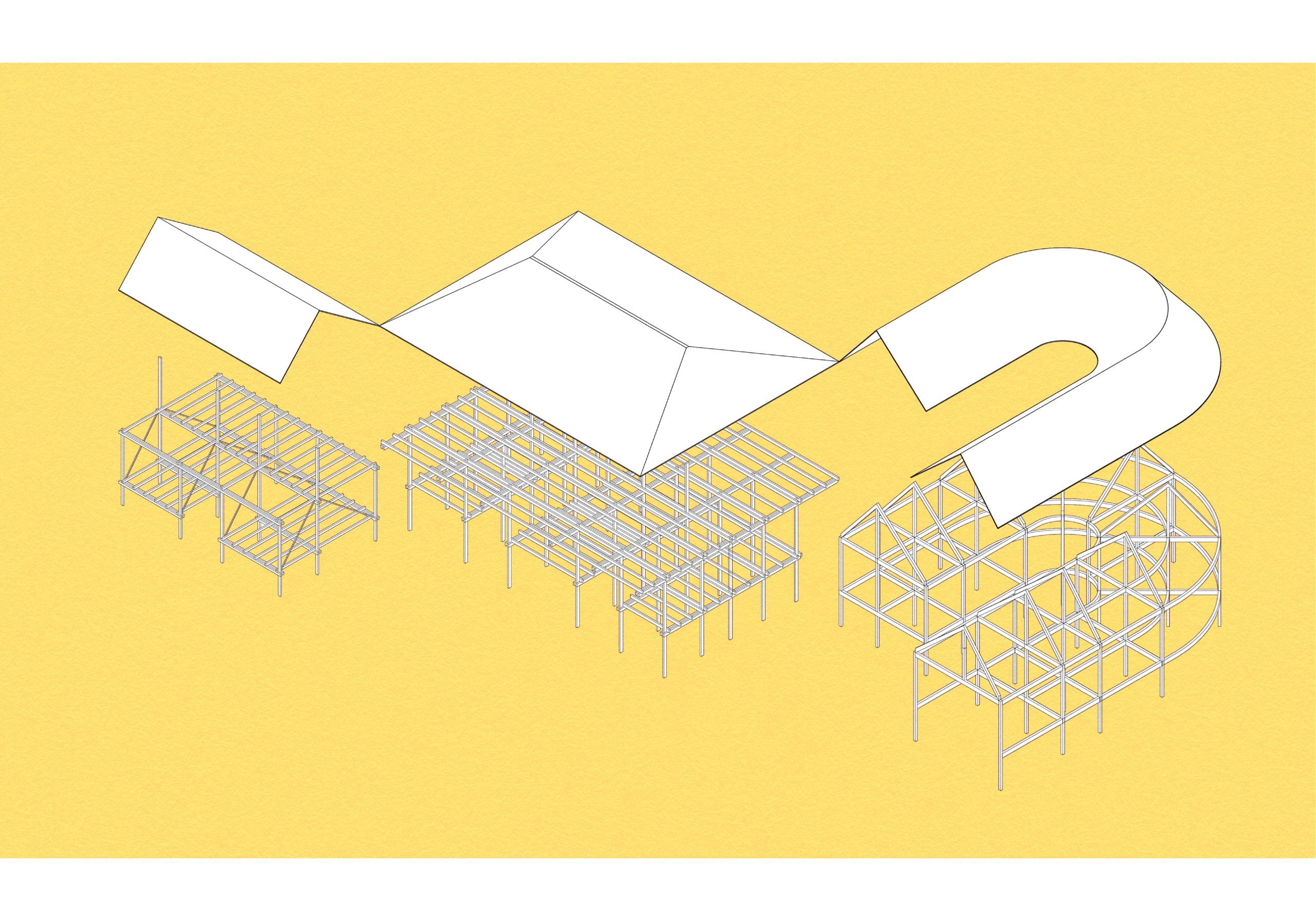

비인간의 행동에서 건축을 시작하는 것, 같은 요소를 공유하는 것, 재해석된 요소에서 또 다른 가능성을 발견하는 것. 새로운 관계는 이 세 명제에서 시작된다. 돼지, 소, 양, 그리고 사람은 각기 다른 몸과 감각으로 세상을 인식한다. 이들의 서로 다른 스케일의 세계는 '지붕'이라는 건축적 요소를 통해 연결된다. 하나의 지붕 아래 유닛의 공간을 나눠 배치함으로써, 인간과 비인간 모두가 머물 수 있는 처마 공간이 확장된다.

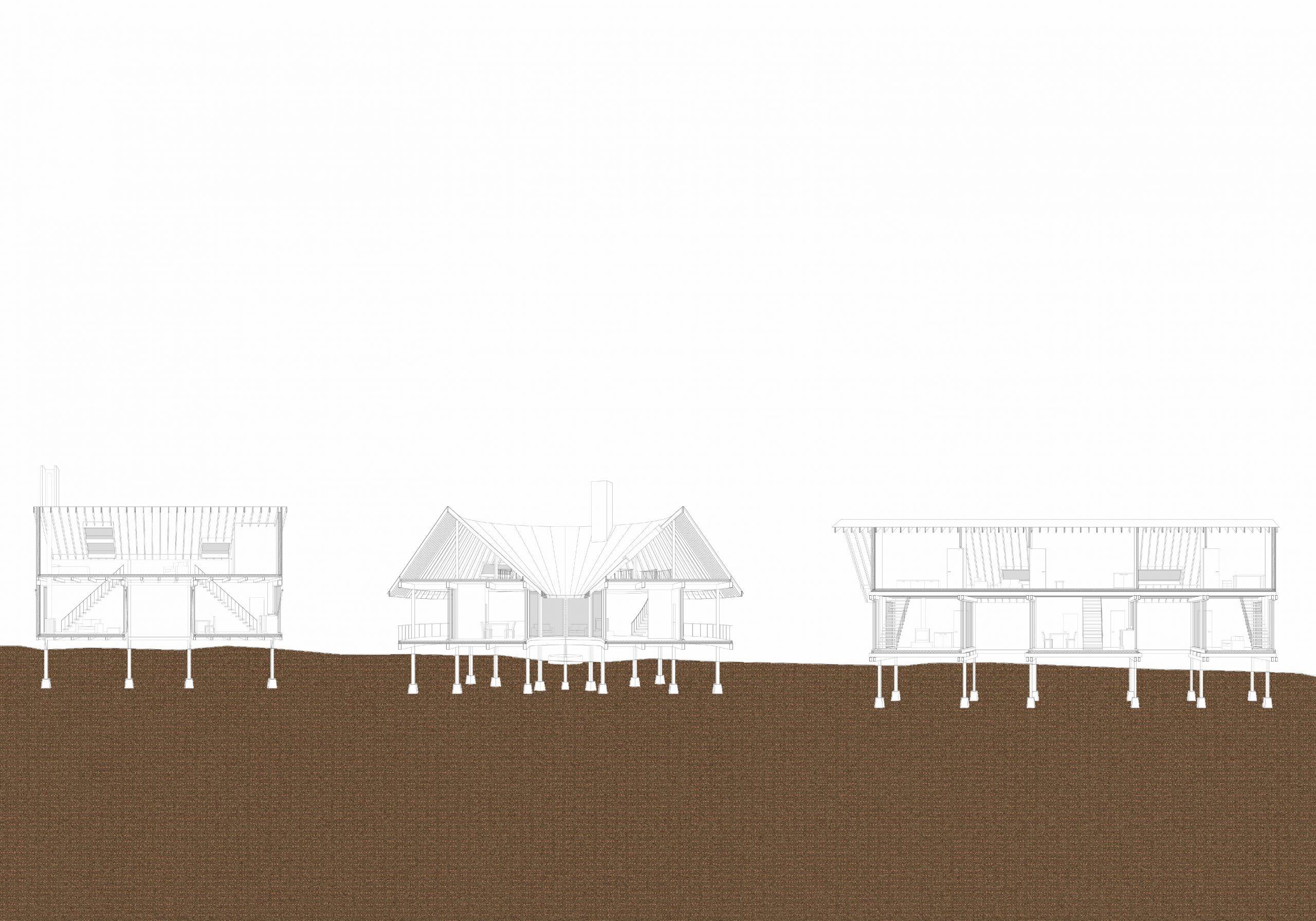

각 동물의 습성과 필요에 맞춰 지붕의 높이와 깊이, 재료를 다르게 설계해, 각자에게 안정감을 제공한다. 돼지는 낮고 깊은 처마로 안정감을 얻고, 소는 높고 얕은 처마로 넓은 시야를 확보한다. 양은 중간 너비의 처마와 루버로 빛과 소음으로부터 보호받는다. 이처럼 각 동물의 감각과 습성에 맞춘 지붕은, 그들이 처마 아래 머물기를 선택하는 이유가 된다. 이 지붕 아래는 인간과 가축이 서로를 인식하고 받아들이는 공간이 된다.

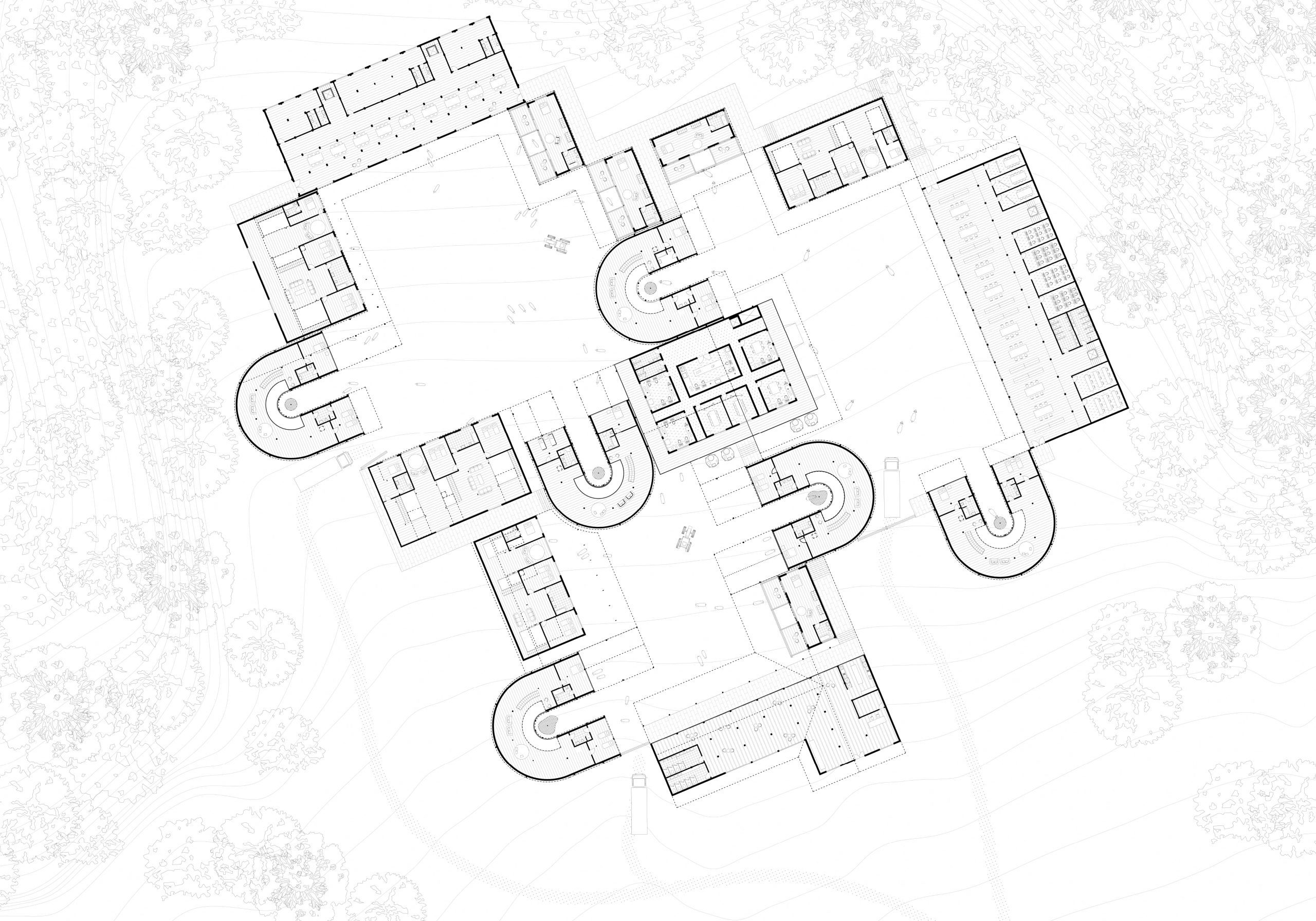

이곳은 강원도 횡성군 둔내면의 돼지던스다. 돼지·소·양이 자리 잡은 마당을 둘러싸듯 3가지 형태의 스테이가 배치되고, 그 중심에 각 가축의 축사와 서울대학교 농학생명과학대학 연구동이 놓인다. 우측에는 농학생명과학대학 도서관과 강의실이, 위쪽엔 농업 일꾼들과 학생들을 위한 기숙사가 자리한다. 스테이는 외부 방문객이 동물의 일상을 곁에서 경험하며 편견을 풀어 갈 통로가 되고, 연구동은 학생과 예비 농업인이 생활·학습·실험을 동시에 수행하며 축산업을 새 시각으로 받아들일 거점이 된다.

지붕과 처마 밑에 생겨난 공간은 가축에게 필요한 지붕을 제공하고, 가축은 스스로 선택하여 자신이 머물 자리를 만든다. 이 선택은 인간의 질서에 가축을 위치시키는 기존의 관계를 넘어 동등한 존재로서 인식을 가능케한다. 동등한 존재로서, 내가 선택한 것이 아니라 또한 선택받을 수 있다는 사실은, 인간과 가축의 관계를 정직하게 바라보게 한다.

Historically, architecture provided shared habitats for humans and livestock — before urban development separated these spaces, driven by economic motives. To maximise profit and minimise costs, livestock farms have resulted in densely-packed, suburban-fringes-bound spaces. Consequently, livestock and their habitats have faded from urban awareness, replaced by misconceptions and prejudices about farming practices.

If architecture could restore visibility to livestock, bridging this perceptual gap, it may be able to challenge prevailing misconceptions and irrational beliefs. Moving beyond human-centric designs to embrace animal presence could redefine relationships between humans and animals, addressing the overlooked crisis of livestock invisibility.

Establishing meaningful connections between humans and non-humans requires sensitivity. Unlike interpersonal relationships, non-humans’ psychological distance does not always correlate with physical proximity. When observing birds from inside a home, they remain perceived as external regardless of actual distance. Introducing wild animals directly into human living spaces, reducing physical proximity greatly, generates mutual discomfort, intensifying feelings of intrusion. Confining animals in cages within human environments may superficially reduce distance, yet ultimately results in hollow ownership when one party’s way of life is disregarded.

By contrast, the relationship formed with birds nesting beneath eaves illustrates a harmonious coexistence. These birds, choosing their nesting sites out of necessity, become equal participants sharing a common structure. Although physically external, their voluntary choice transforms our perception, acknowledging them as equals in a shared space. Historically, barns confined livestock within human-imposed boundaries. The present proposal seeks a new relationship reminiscent of birds under eaves—one rooted in coexistence rather than ownership.

This new approach centres architecture around animal behaviours, shared design elements, and reinterpreted forms. Pigs, cows, sheep, and humans each perceive the world uniquely due to distinct physical attributes and sensory experiences. Despite these differences, they can coexist beneath a shared architectural element: the roof. Thoughtfully designed roofs, tailored to each animal’s needs, create a unified yet differentiated habitat.

Pigs prefer low and deep eaves that offer security; cows thrive under higher, shallow eaves that permit expansive views; sheep require moderate eaves with louvers to soften intense light and noise. By aligning design with specific animal behaviours and senses, the animals naturally choose to inhabit these spaces, fostering mutual recognition and acceptance between humans and animals.

This is Porkitecture, located in Dunnae-myeon, Hoengseong-gun of Gangwon Province. Accommodations surround a central courtyard for pigs, cows, and sheep, integrating animal barns and the Seoul National University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences research centre. Facilities such as a library, classrooms, and dormitories support both visitors and researchers. These spaces offer visitors immersive experiences to challenge biases and provide researchers with opportunities to explore innovative approaches to livestock farming.

Roofs and eaves create environments where animals can autonomously choose their habitats. This choice redefines human-animal relationships, fostering equality and mutual respect. Recognising animals not merely as beings humans select, but as entities capable of selecting humans in return, encourages a genuine reflection on our relationship.

Ultimately, Porkitecture invites reconsideration of overlooked presences, illuminating hidden realities and encouraging thoughtful exploration of coexistence with other beings.